The Juggler

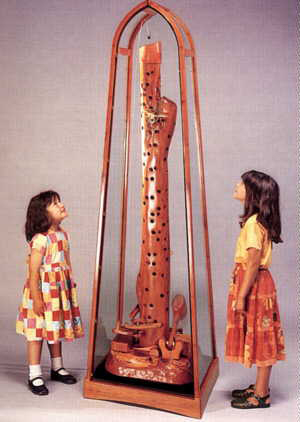

In the folds of the Purbeck Hills in Dorset there is an old stone farmhouse. Look in one of its outlying barns and you will find a solitary man and his clock. His name is David Bowerman, he is a craftsman in wood, and his clock is called the 'Juggler'.

David might seem a little out of touch with his time. He refers nostalgically to the court of King Louis, when furniture makers were "...at the top of the tree, the most venerated craftsmen making the ultimate status symbols" - and they often got a pop star salary as their reward. David enjoyed woodwork more than anything at school, studied it at Parnham House under John Makepeace, and for the past 17 years has worked alone, making English hardwoods into bespoke furniture for a small, discerning clientele.

The 'Juggler' is a direct result of a short period when he was 'guest lecturer' on a Design Course at Bournemouth University. The students' brief was to design a clock-as-sculpture, and since David had already made two fine 'regulators' in traditional 18th century style he was considered suitable for the job. However, things didn't go to plan. The students backed off when they discovered the depth of his radical, complex solutions. But with the seed planted David decided to go ahead and pursue the project anyway, and embarked on creating his own unique, original timepiece.

Three years and more than 2000 hours of skilled labour later - he carefully logs all work time in a battered notebook - David feels the 'Juggler' is virtually complete. But why did it take so long, and more important how did it get that name? To get some idea of the time, you should first find an ancient yew, blown over in a country graveyard. Cut off a suitably stout branch which will form a 6ft (1.8m) high trunk. Remove all bark and sapwood, sand smooth, and polish thoroughly with teak oil and wax. Next, drill a mass of 3/4in (1.9cm) holes through the trunk, as if a demented woodpecker had attacked the wood, and sand the inside of each hole absolutely smooth.

To continue, affix a clock movement, which you have hand-made in brass and which has more recently also been gilded with 24 carat gold - it doesn't need polishing and it won't oxidise.That was the easy bit which relied on David's immense bank of skill with the properties of English wood. The real problem was getting it to work, particularly when he had dreamt up the craziest mechanical system possible which goes well into the realms of Heath-Robinson and Emmett. Picture this: the 'Juggler' is loaded with a mass of heavy 5/8in (1.6cm) steel balls which make a never ending journey from the top to the bottom of the trunk and back up again. Each ball takes 47 seconds to find its way downhill through the maze of holes that pepper the trunk.

As one reaches the bottom, it triggers the release of the next ball and advances the clock movement. After fifteen minutes, a total of 19 balls have travelled from top to bottom. The 19th ball in the cycle is principal assistant to the 'Juggler', triggering a reaction which as David well knows "Never fails to brings a big smile to everyone's face, from young children to octogenarians". As the clock strikes the quarter, all hell is let loose. A cunningly hidden electric motor (with optional solar supply) powers up a mallet which deftly hits each steel ball high into the air. 'Thwack!'. A ball shoots skyward like a rocket, reaches its zenith high above the clock, and then drops and plops gracefully into the leather cup mounted on top of the trunk which helps cushion the impact. Nineteen times this happens, and it has to be seen to be believed.

As can be imagined, it took a great deal of time and intense head scratching to persuade this bizarre operating system to work.

David remembers it as "...an absolute nightmare - a fool rushing in where angels fear to tread", and the ceiling of his workshop bears witness to the long process of trial and error as it is literally peppered with dents and felt-tip crosses marking the path of many hundreds of wayward balls.

The 'Juggler' is always second-perfect because it has a radio receiver tucked away inside which listens to the national atomic clock and keeps a constant check on the time.

David is keen to use the experience gained on these projects to design and make other feature clocks. It seems an odd paradox that while horological technology has made huge strides in the last few decades, the visual design of most mechanical clocks is largely unchanged. This is a gap in the market that offers endless possibilities and David is a man who can make it happen.

The Juggler's clock face